How to Pick Your Next Gig: Evaluating Startups - Part II

14 Aug 2017

This is a continuation of a previous blog post, the first part of which you can read here.

The criteria, continued

Investor pedigree

If I was looking for a job, and I saw that a company was backed by Sequoia Capital, I might just be tempted to apply, knowing nothing else about the company.

Here’s a list of companies whose Series A or B rounds (or both) were led by Sequoia: Apple, Google, Yahoo!, Stripe, Dropbox, YouTube, Instagram, Airbnb, and WhatsApp.

Of Sequoia’s over 1000 investments since 1972, 209 companies have been acquired and 69 have IPOed. Their mission statement:

The creative spirits. The underdogs. The resolute. The determined. The outsiders. The defiant. The independent thinkers. The fighters and the true believers.

These are the founders with whom we partner. They’re extremely rare. And we’re ecstatic when we find them…

We’re serious about our work, and carefully choose the words to describe it. Terms like “deal” or “exit” are forbidden. And while we’re sometimes called investors, that is not our frame of mind. We consider ourselves partners for the long term.

We help the daring build legendary companies.

This is good marketing, but also really does capture the ethos of Silicon Valley.

This is a criteria that I would intuitively award 5 points, but that even investors themselves would warn against overvaluing. So I compromised, and gave it 4.5 points.

Silicon Valley has a hierarchy in its investors. The top-tier is generally agreed to consist of: Sequoia, Kleiner Perkins (KPCB), Greylock, Benchmark, Accel, and Andreessen Horowitz.1 Other well-known venture firms include General Catalyst, New Enterprise Associates (NEA), and Lightspeed. These are the venture capital firms that, in general, attract the best founders, win the best deals, and show the highest returns.

Even the best firms, however, often miss great deals, so the failure to raise funding from one of these groups does not necessarily imply weakness. This is particularly true of companies founded outside of the U.S., and of very promising founders who may have weaker connections to Silicon Valley’s old guard (though these firms have gotten pretty good at identifying unknown upstarts).

On the flip side, not all companies funded by top-tier venture firms are excellent places to work. It is the nature of their business that venture capital firms will invest in a large number of companies that will fail. More than that, promising companies can sometimes degenerate if their growth is achieved at the cost of their culture or values. Regardless of who is backing them, such startups are best avoided.

Funding history

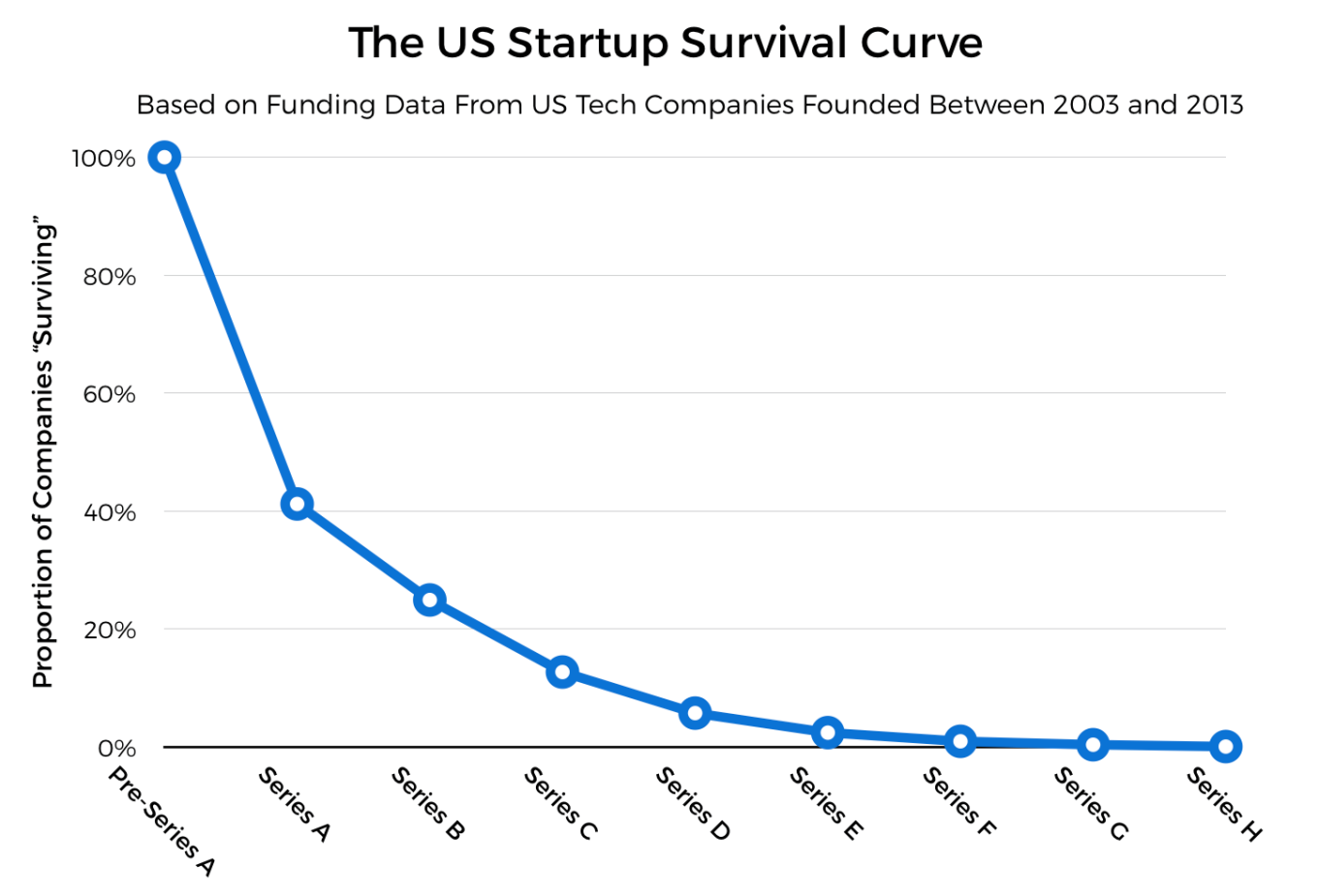

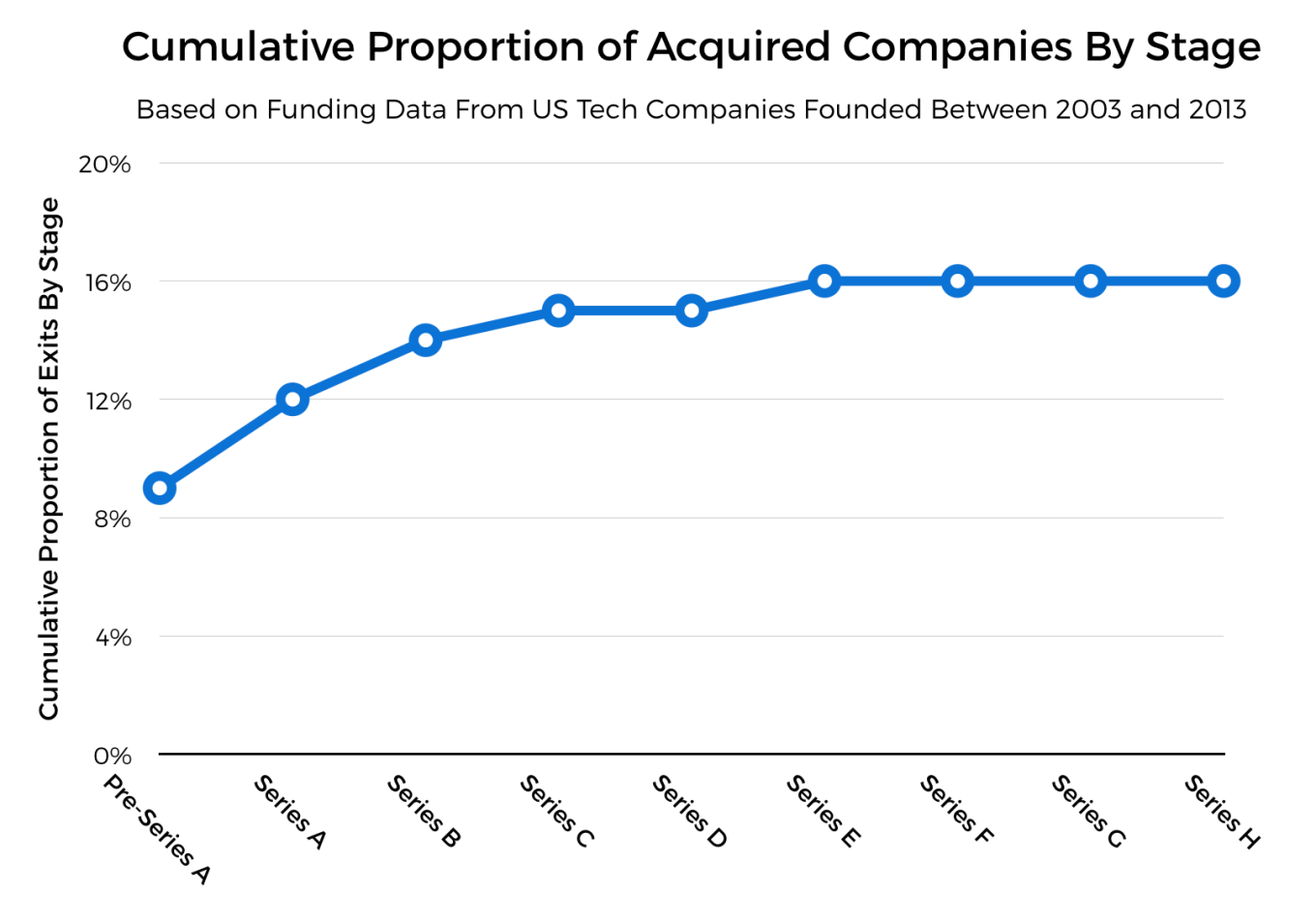

The funding statistics in this section are based on a 2017 article by TechCrunch that looked at 15,600 U.S.-based tech companies founded between 2003 and 2013.

As a sanity check, I also compared these numbers with those from a similar Business Insider article from 2016. The BI funding statistics are slightly more conservative.

The number of rounds of funding raised by a company is a decent indicator of how much risk the startup has neutralized, or in other words, how likely the company is to succeed at some level.

This doesn’t mean that it is always better to join a company that has raised a Series C round over a company that has only raised a B round, because there is a tradeoff. The Series C company will be offering a smaller equity share, possibility significantly so, and thus less potential upside. In addition, some types of funding rounds can actually be indicative of problems in the company – notably, down rounds and debt financing.2

A company that has raised no external funding should be considered “extremely high risk”, and not being offered founder-level equity at such a company should be met with extreme skepticism. (Especially because you are likely to be working for little to no pay for a while.)

A company that has raised a seed round is officially a funded startup, but is still “high risk”, as only about 40% of seed-funded companies go on to raise Series A rounds, and only about 9% get acquired. Seeds rounds are usually raised from individual investors (i.e. angels) or specialized funds, such as Y Combinator, Founders Fund, and SV Angel, and generally involve on the order of $0.5-1 million in capital.

A company that has raised a Series A round should be considered “moderate risk”. Of companies that raise an A round, about 62.5% go on to raise a Series B round, and 7.5% get acquired, which implies that the other 30% likely die. In terms of career growth and financial upside, this is probably the best time to join a startup that scores highly on all of the other criteria. Series A companies still have high growth potential, and yet have been formally validated by a group whose full-time job it is to evaluate early-stage startups. As a prospective employee, you now have an additional data point: the reputation of the venture capital firm that led the Series A round.

Series B round companies should be considered “moderate to low risk”.3 For one, companies that have raised a Series B are almost always generating revenue. Series B round investors look for evidence of healthy growth in users or customers since the A round, meaning that Series B companies have been validated not only on company fundamentals (team, product, market) but also on more complex signals, such as product-market fit.

When evaluating a startup on its funding history, an important factor to consider is when the last round of funding was raised. A Series B company founded in 2005 that hasn’t raised any venture capital since 2008, and has not IPOed, is either 1) reliant on its own revenue, and likely slow growing (i.e. not really a startup), or 2) approaching death.4

A point to note: companies that have raised a Series B round or beyond should be offering a base salary that is competitive with that offered by larger, public companies. For new college grads, the average base salary offered by top-tier tech companies based in San Francisco was $110,000, as of mid-2017. Take this figure with a grain of salt (and, of course, don’t neglect cost of living adjustments), but if you’re being offered much less, you’re either at a company with an unusual compensation structure (and should be offered a significantly above-average equity grant), or are not being made a fair offer.5

Note also that raising an advanced stage of funding (e.g. a Series D or E round) doesn’t signify with certainty that the company is immune from death. Silicon Valley history is replete with examples of startups that were valued at or over $1 billion, and were later acquired for much less than that (e.g. Gilt Groupe, One Kings Lane, LivingSocial) - i.e. companies that raised a lot of capital, and then floundered. So I equate rounds of funding with neutralized risk simply as a rough heuristic for estimating the risk-reward tradeoff involved in joining a company.

I would recommend asking a founder or executive the following question during the interview process: what is company’s current projected runway? This is an estimate for how long the company could stay afloat, given the cash in its bank and its current rate of spending (i.e. burn rate), were it not to raise any more funding. Asking this question definitely does not constitute a faux pax, and an evasive answer is a bad sign.

Location

Every year, Wealthfront identifies a set of “career-launching” tech companies for aspiring young professionals by surveying the partners of 14 top venture capital firms. The qualifications for making the list are: 1) a revenue run rate between $20-300 million, and 2) a growth trajectory of over 50% over the next three to four years.

Wealthfront’s 2017 posting identifies 132 such companies. Of these, about 61% are located in the San Francisco Bay Area, followed by 10% in New York, 5% in Boston, another 5% in Southern California, and 4% in Seattle. Of the Bay Area companies, about 58% are located in San Francisco itself.

Treat location as a low-pass filter on a company’s prospects. A company based out of San Francisco, Palo Alto, Menlo Park, or Mountain View is obviously not guaranteed to be successful, but a company not headquartered in the Bay Area or New York (and maybe Boston, Seattle, or LA) is going to be fighting an uphill battle finding investors, attracting and retaining strong employees, and (in many cases) connecting with its early adopters.

Personal fit

I want to play devil’s advocate and argue that what a company builds may not actually be that indicative of whether the company would be a good fit for you. Let’s say you’re interested in machine learning, but you think enterprise tech is super boring.

You could find a job at an MLaaS6 company which builds tools to help genomics researchers more efficiently construct data analytics pipelines. You thought you’d never enter a world in which companies use aggressive sales tactics to upsell overpriced software to other companies, but you come to realize that writing tools for a small number of clients who place extreme value in the products you build for them is actually quite fulfilling.

You could also find a job at a consumer-facing company that uses machine learning to personalize the content it serves users, and to customize the ad copy it shows them based on the cookie-infested websites they visit. You realize that linear regressions still do pretty well on these kinds of tasks, and though you were initially very excited about contributing to a service that your friends use, it is not actually super riveting in the day-to-day to work there.

The point here is that you should be open-minded about the kinds of problems you could be interested in, and the kinds of work you’d like to do. Don’t judge companies solely on their one-sentence mission statements. Instead, take the time to understand what the startup really does, why the problem they’re solving is an important one, and what the immediate and future market for their work is.

Relatedly, how much does the nature of the work that you do - full-stack, backend, cloud platform, data science - matter? Your interests matter, and developing an area of competitive advantage as an employee can matter. In startups, however, initial job title and responsibilities are generally dwarfed in importance by the pace of the company’s growth. A small, fast growing company will require you to wear many hats, regardless of what your job description says, and assuming it is well-managed, should reward strong performance commensurately.

In this talk, Dustin Moskovitz, co-founder of Facebook and co-founder of Asana, makes the very relevant point that intelligent young people often overvalue working on the most challenging problems. His exact words:

A lot of graduating students think I just want to work on the hardest problems. If you are one of these people, I predict that you’re going to change your perspective over time. I think that’s kind of like a student mentality, of challenging yourself, and proving that you’re capable of it. But as you get older, other things start to become important, like personal fulfillment, what are you going to be proud of, what are you going to want to tell your kids about, or your grandkids about, one day.

How will the work that you do add value to the world? As Moskovitz says, this is not a given for every startup. Life is too short to work for a company that does not do work that matters to you, and that matters period.

Product quality

Last but not least is the product itself. What is the company building?

Two questions here:

How much do users (customers) love the product? Do they tell their friends (other employees) about it?

Is the product fundamentally inventive or dramatically better than its substitutes in the market today? The most successful companies tend to be those that shift paradigms, either by building:

0 to 1 products. These are services that are the first in their kind – not derivatives of existing ideas (e.g. Amazon, Uber, Airbnb).

10x products. These are services that are at least an order-of-magnitude (“10x”) faster or cheaper than their substitutes today (e.g. Google vs. Alta Vista (1998)).

A paradox of entrepreneurship is that it is often easier to build a company to solve a hard problem than an easy one. Space exploration, driverless cars, curing infectious disease - these ideas excite and attract smart people, and inspire loyalty in trying times.

That said, do not discount products that seem like toys as trivialities. Facebook was once just a tool for Harvard students to stalk each other, and Snapchat was something worse. Today, Facebook connects two billion people around the world, and Snapchat enables a hundred million to communicate more authentically.

This is where the first criteria becomes useful. Early Facebook users spent hours clicking from profile to profile (okay, maybe some people still do this), so engrossing was the data that Facebook had made available on their friends. In its IPO filing, Snap revealed that the average daily active Snapchat user opens the app 18 times a day.

Of course this discussion is more relevant to consumer companies. For enterprise startups, it might be worth asking early customers what they feel about the product. What pain points does it solve for them? Will the solution scale?

Closing thoughts

Verdict

So what’s the verdict? Here are the criteria, as scored in this blog post:

- Investor pedigree - 4.5 points

- Strength of early employees - 4.5 points

- Strength of founders - 4 points

- Personal fit - 4 points

- Current traction - 3.5 points

- Funding history - 3.5 points

- Product quality - 3.5 points

- Growth rate - 3 points

- Location - 2.5 points

- Number of employees - 2 points

I deemed investor pedigree and strength of early employees to be the most important criteria (4.5 points), followed by strength of founders and personal fit (4 points), and then the current traction, funding history, and product quality (3.5 points).

One question one might ask is why the “strength of the early employees” is more important than the “strength of the founders”. Granted that strength is a subjective word, the short answer here is while it is the market that selects the founders, it is the founders who hire the employees and build the company.

So the strength of the early employees reflects on the judgment of the founders, the promise of their initial work, and their ability to inspire and attract great people. Arguably, these attributes together (or their absence) are what will make or break the company, given a promising early tailwind (the market).

Besides the strength of the team (founders, investors, employees), the next most important criteria is broadly the “traction” and velocity of the company, which is reflected in the product traction, the funding history, the product quality, and the growth rate.

A historical perspective

Through the dot com bust and the rise of mobile phones, three survivors emerged from the Internet era: Google, Facebook, and Amazon. Google indexes the world’s information, Facebook indexes the world’s people, and Amazon indexes the world’s products. Though on decidedly shakier grounds, the mobile era has spawned its own behemoths. The three enabling forces here are messaging (i.e. low-latency, mobile web-based chat), the camera (i.e. the dual-facing, integrated recording device), and location (i.e. high-precision global GPS), and their flag-bearers WhatsApp, Instagram/Snap, and Uber/Lyft.

In a similar way, each technological wave spawns companies of all kinds, but the most persisting are the ones that encapsulate the simplest, most fundamental ideas. This is always easier to spot in retrospect, of course. The best companies tend to execute on ruthlessly narrow domains to start out, and then expand rapidly to realize a wider potential. Early Google ranked textual pages. Early Facebook connected college students. Early Amazon sold books. Today, Google is using AI to drive cars, Facebook is beaming down Wi-Fi to the world’s disconnected, and Amazon is launching drones to automate delivery.

Though each of the three had humble origins, even in their early days you would have found markers of greatness. The most important such marker is explosive growth. The best consumer companies are a bit like child prodigies – they grow faster than you would think possible, racing past milestones that other, more mature companies, run by professional CEOs and seasoned C-suites, struggled to reach. Of course, like child prodigies, some flame out early (e.g. Yik Yak), while others fail to mature into healthy, cash-flow positive adults (e.g. Twitter). But every decade, two or three chart their way to adulthood fame.

Takeaways

I’m not suggesting that a startup is only worth joining if it resembles Google circa 2000 or Facebook circa 2006, but studying the characteristics of the really successful companies is still a useful exercise. Not every startup has a glorified origin story. Companies such as Airbnb, SpaceX, and Tesla weathered many near-death experiences in their early days. In more cases than not, the cost of greatness is great struggle.

So while you can’t compare every company to Instagram, which crossed 100,000 users less than a week after its launch in October 2010, you can learn to spot the markers that signal that a company is promising, and on a trajectory that could take you places. I hope this piece serves as a useful guide at least for the common cases, if not for spotting the next big tech company in its infancy.

Thanks to Adrian Colyer, Chris Kuenne, Hansen Qian, Andrew Ng, and Sanjay Jain for reviewing drafts of this post.

Footnotes

Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) is a bit of an outlier. Founded in 2009, it is the only venture capital firm started after 1995 to make this list. Being the newest of the lot, a16z has more to prove, but in terms of prestige, reputation, and network centrality it is second-to-none. Some of its highest profile exits/IPOs include Groupon, Skype, Zynga, Nicira, Oculus VR, and GitHub.↩︎

Two kinds of funding rounds can actually be indicative of problems in a company. The first is down rounds. These are almost always bad, as they imply that a company was obliged to raise funding to stay alive, but had to do so at a lower valuation than in its previous round of funding - something that is bad for all existing shareholders of the company. The second kind is debt financing. In such a round, a company raises debt, which must be paid back with interest, instead of ordinary capital. This has become a common practice among very mature private companies, such as Uber and Snap (before its IPO), which often need more cash, but either do not want to further dilute shareholders or cannot find a bank willing or able to invest at their current valuation. The general consensus is that debt financing in later fundraising rounds is more acceptable than debt financing early on, but this is an intricate topic, and it’s worth understanding the full implications of a potential employer’s funding history. In particular, raising a form of capital called convertible debt in a seed round can force a company into bankruptcy if it fails to raise a Series A round within 12-18 months of the seed round. Recently, there has been move toward a more founder-friendly instrument called convertible equity, which does not need to be repaid and does not accumulate interest. Convertible equity retains the primary advantage of convertible debt: it delays valuation discussions until a startup is mature enough to be accurately priced. This can be complicated, however, by valuation caps, a feature very often demanded by early stage investors.↩︎

In this discussion, I use terms such as “high risk” and “low risk”, but defining risk is tricky, because the definition of success for a company’s employees is stricter than the definition of success for the founders and early investors. As an example, consider a liquidity event, say a $250 million acquisition, that occurs after a Series C round that values the company at $350 million. A $250 million acquisition is great news for the founders, who will likely earn $25-50 million a piece on their equity, and for the seed-stage and Series A round investors. But it is definitely not good news for the Series C round investors, and may not be a win for later employees, either. Employees who joined right after the Series C round were granted four years of stock options worth (say) $60,000 at the $350 million valuation, options now worth about $45,000. In the context of (say) a $115,000 annual base salary, this is not a huge monetary loss, but for a talented engineer, spending several years at such a company entails a separate, much higher opportunity cost.↩︎

An example of a startup that has done very well without raising much external capital is Atlassian, a Sydney, Australia-based company that builds productivity software (e.g. Jira, Confluence) for developers. Founded in 2002, Atlassian has been profitable since 2005, and in 2015, IPOed on the NASDAQ stock exchange at a $4.3 billion valuation. In 2010, Atlassian raised $60 million in secondary financing from Accel Partners. This was a very unusual kind of funding round - the company already had $55 million in the bank, and raised the money as a way to offer employees liquidity for their options, and to bring in an external board member from Accel.↩︎

Where public companies and startups differ is in what they offer on top of the base salary. While public companies or late-stage startups may offer a cash bonus and RSUs (which become publicly tradable stock options on vesting), startups generally compensate via stock options, which must be purchased from the company at an exercise (strike) price, and which can generally only be sold once a company has gone public or gotten acquired. In some cases, however, it is possible to sell stock options on a private secondary market (e.g. to another venture capital firm), or back to the company during a stock buyback program.↩︎

Okay, I made this term up (MLaaS = machine learning as a service), but a quick google search indicates that we may not actually be too far off from this phrase entering the canon.↩︎

Read More

- 2022 Job Search (21 Jun 2022)

- 2021 Books (01 Jan 2022)

- Regret Minimization (08 Sep 2021)

- Required Reading (16 Jul 2021)

- Revolutions (14 Oct 2017)

- On Computer Science (15 Sep 2017)

- Samvit's Guide to the World Wide Web (28 Aug 2017)

- How to Pick Your Next Gig: Evaluating Startups - Part I (14 Aug 2017)

- A Brief Primer: Stochastic Gradient Descent (20 Jul 2017)

- Why Parallelism? An Example from Deep Reinforcement Learning (06 Jul 2017)