Why Parallelism? An Example from Deep Reinforcement Learning

06 Jul 2017

In this post, I introduce the Google DeepMind paper “Massively Parallel Methods for Deep Reinforcement Learning” from ICML 2015, and discuss the motivation behind developing parallel implementations of useful algorithms.

Paper contributions

This paper presents a distributed implementation, called Gorila, of the Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithm, which applies deep neural networks to the problem of reinforcement learning (RL). The algorithm, which was published in Nature, uses a deep convolutional network to approximate the optimal action-value function, which guides an RL agent’s behavior. The core breakthrough: the agent was trained to play a set of Atari 2600 computer games based solely on the pixels of still frames and associated scores, and yet beat all previous implementations, achieving a level of performance comparable to that of professional human players.

The authors of this paper used Gorila to play 49 Atari 2600 games in two different test settings, and did even better, beating the non-distributed DQN implementation in 31 out of 49 games in the first, and 41 out of 49 games in the second. Notably, to reach these results, their system was trained for a wall-clock time that was roughly an order of magnitude less than that required by the single GPU implementation.

Parallelization

Gorila achieves these results by introducing parallelization along three axes:

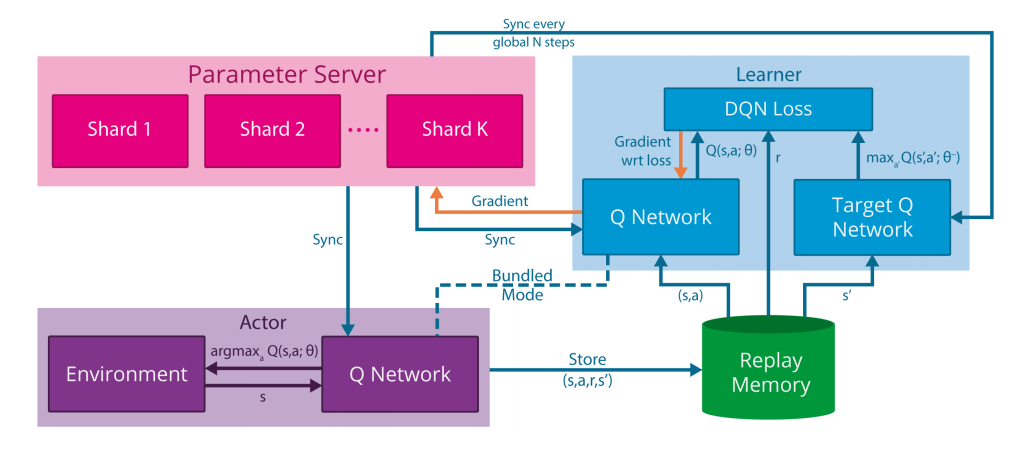

Actors - In an RL algorithm, actors are the agents that explore an environment, and reap reward as they do so. Gorila supports \(N_{act}\) actors which operate in parallel on \(N_{act}\) instantiations of the same environment. Each actor generates its own trajectory of experience on the environment, which can be stored both in local memory and in a global memory.

Learners - Learners sample experience from the local or global store, and apply an RL algorithm such as DQN to it, generating a gradient vector \(g_i\) to be communicated to the parameter server (see third point). The parameter server uses these gradient vectors to update a master copy of the Q-network. Gorila supports \(N_{learn}\) concurrent learner processes, each of which contains a replica of the Q-network, and computes a gradient update from an independently drawn sample of experience at each iteration.

Parameter server - The parameter server, which serves the role of a master node, maintains a distributed representation of the Q-network, with the parameter vector θ split across the \(N_{param}\) machines of the server. The parameter server receives gradient updates from the learners, and each of the \(N_{param}\) machines applies the appropriate updates to the subset of θ that it is responsible for. This process of applying updates in a distributed manner follows an asynchronous variant of stochastic gradient descent. The parameter server periodically sends an updated copy of the Q-network to each learner.

So what?

Why is this significant? It seems obvious that if you throw more computational power at a problem (i.e. by running the algorithm on a cluster of CPUs, as opposed to a single node), performance (as measured by accuracy or head-to-head performance, given comparable training time) should improve, or alternatively, that the required training time should decrease (given comparable results). In general, what is the point of a paper that presents a distributed implementation of a well-known algorithm, and claims that performance improved?

Actually, the contribution can be of one of two flavors:

- Demonstrating that a particular algorithm can be implemented fruitfully in a distributed fashion. Emphatically, this is not always the case. Such a paper might show that the throughput of the system scales linearly with the level of parallelization (e.g. number of concurrent processes used), which suggests that a large portion of the computation is parallelizable. Notably, even a sub-linear improvement can be a win, as achieving any kind of speedup with a distributed design requires overcoming inherent communication and synchronization-related overheads.

Such results are particularly valued when there are particular, demanding performance objectives that must be met. Monitoring a large data stream in real-time to flag anomalies may require greater processing throughput than a single node system can support. Supporting interactive queries on a massive data set may necessitate lower response latencies than a non-parallel implementation can guarantee. In machine learning, in particular, there are often significant returns to improved performance, with faster training times allowing for rapid iteration during model development, or simply the use of more training data.

Secondly, the ability to parallelize computation often allows for significant cost savings. The canonical example of this is Google’s early decision to execute search indexing on clusters of commodity machines, as opposed to expensive mainframes. Today, the relevant comparison may be the tradeoff between running a data-parallel computation on a cluster of CPUs versus on one or more high-performance GPUs. Using Amazon EC2 on-demand pricing as a rough proxy for hardware and power costs, renting a starter-tier GPU instance, the p2.xlarge, costs $0.90 per hour, while a comparable1 general-purpose CPU instance, the m4.xlarge, costs only $0.20 per hour. This is admittedly a coarse comparison, but the almost 5x price spread suggests that outside of a few highly specialized applications, CPU clusters may still be the way to go. Note that analysis does not even include the software challenges of rewriting code to take advantage of a GPU’s single-purpose, SIMD architecture.

- Demonstrating that the distributed variant of an algorithm can yield a superlinear speedup. This is rarer, but often possible. A relevant example of this is found in another DeepMind paper, “Asynchronous Methods for Deep Reinforcement Learning,” from ICML 2016, which, as a side note, presents an asynchronous 1-step Q-learning algorithm that achieves a 24x performance improvement, using 16 threads, over a single-threaded implementation.

How is superlinear speedup possible? Here’s a basic example: if an algorithm involves executing a computation on a large data set, parallelizing it (e.g. via a master-worker approach) could reduce or eliminate disk accesses, if the resulting data partitions now fit into each worker machine’s main memory.

In the case of reinforcement learning, the experiments with asynchronous 1-step Q-learning showed that less training data was needed in aggregate to reach score parity as more parallel actor-learners were used. The authors believe this superlinear behavior stems from the use of different exploration policies on different processes, which leads to parameter updates that are less correlated in time than if a single agent were to explore the environment sequentially. In other words, using more actor-learners leads to collecting experience that is more “diverse,” leading to faster convergence of stochastic gradient descent.2

As these examples indicate, superlinearity can stem from both systems and algorithmic optimizations unlocked by parallelization. Such papers are valuable because they suggest avenues toward substantially better (e.g. “10x”) system architectures or algorithms.

Note also that by Amdahl’s law, superlinearity can only hold for so long; as the number of processors grows, the speedup achieved by parallelization approaches a fixed constant, with the non-parallelizable component of the task becoming the bottleneck. Even if a particular computation is completely parallelizable, the speedup factor approaches a linear asymptote.

Of these two, Gorila falls in the first category, as it demonstrates how a parallelized implementation of the DQN algorithm can outperform the original, serial implementation, but does not claim any particular asymptotic behavior. Remarkably, the authors were able to beat the single GPU implementation, which was trained for 12-14 days, in 38 out of the 49 games considered after just 1.5 days of training!

Thanks to Robert Nishihara, Roy Fox, and Sanjay Jain for reviewing drafts of this post.

Footnotes

I used the Amazon ECU and vCPU designations as a rough benchmark for instance compute power. ECU is an abbreviation for Elastic Compute Unit, which Amazon is phasing out for the more standard vCPU (virtual CPU) designation.

The p2.xlarge GPU instance consists of 4 vCPUs and 12 ECUs. The closest comparable CPU instance I found, the m4.xlarge, consists of 4 vCPUs and 13 ECUs.

Note that the r3.xlarge, a comparable memory-optimized CPU instance (4 vCPUs, 13 ECUs), costs $0.333 per hour, compared to $0.90 per hour for the GPU instance.↩︎To be completely precise, asynchronous 1-step Q-learning does not require the use of parallel execution threads. A similar effect would be seen if a serial machine were to simulate parallelism, by maintaining the state for multiple instantiations of the algorithm in memory, and running the exploration policies in a round-robin fashion on the instances. (Incidentally, this is also how a single-core machine would support the abstraction of multiple threads.) What precludes this in practice, however, is the lack of sufficient RAM on a single-core machine to keep so much state in memory.↩︎

Read More

- 2022 Job Search (21 Jun 2022)

- 2021 Books (01 Jan 2022)

- Regret Minimization (08 Sep 2021)

- Required Reading (16 Jul 2021)

- Revolutions (14 Oct 2017)

- On Computer Science (15 Sep 2017)

- Samvit's Guide to the World Wide Web (28 Aug 2017)

- How to Pick Your Next Gig: Evaluating Startups - Part II (14 Aug 2017)

- How to Pick Your Next Gig: Evaluating Startups - Part I (14 Aug 2017)

- A Brief Primer: Stochastic Gradient Descent (20 Jul 2017)